The Relationship Between Landscape and Home for Palestinian Artists

by Roula Seikaly

When San Francisco-based curator and educator Dr. Kathy Zarur was approached by Hilary Rand, program facilitator of the suggestively titled nonprofit Institute Of advanced Uncertainty, Zarur was intrigued. Rand’s proposition presented an opportunity for Zarur to achieve a long-sought goal: curating a group exhibition of contemporary Palestinian art that addresses landscape. Preoccupations: Palestinian Landscapes is that goal beautifully realized.

“Landscape” is, in equal parts, a complicated psychological and geographic construct. Its American origin story, for example, is heavily influenced by the ideological notion that the land (and the indigenous populations who live on it) must be civilized (subjugated and exploited) by their (white) cultural superiors. Visual art — first painting, and then photography — was a powerful tool as the European colonial agenda to “settle” the North American continent was executed. For those who face colonization or expulsion, landscape is an equally potent idea. It represents a heady mix of self, family, home, community, and a sense of belonging in the world, none of which will be surrendered.

Since 1948, a dispute over land now occupied by Israel has been one of the entrenched geopolitical conflicts on the planet. Palestinians who were driven from their homes constitute one of the world’s long-standing refugee populations, and the fight to retain the few state-granted rights and land that is left to them is ongoing. Resolution of this profoundly complex question has bedeviled multiple generations on both sides. With that in mind, Zarur’s choice of Preoccupations as the exhibition title is more than fitting.

In the work of C. Gazaleh and Suhad Khatib, Palestine is an embodied experience. Best known as a muralist, Gazaleh’s densely-packed drawings incorporate Arabic calligraphy and graffiti. Somber faces of beautiful women and handsome men that are embedded in the graphic tangle stare back at the viewer. It is as if the figures are one with the text, which could be a poem, or political analysis, or a love letter that was written but never sent. The text threatens to overwhelm the figures, much as political rhetoric — viability of a two-state solution, the right of refugee return, East Jerusalem as Palestine’s capital city — exhausts those who live it day to day. In “Flight Over Jerusalem”(2015), the female figure floats above and away from the Jerusalem skyline, free to inhabit a world without oppression.

Suhad Khatib’s ink paintings likewise evoke fantasy and dream, treating landscape as an extension of self. In “The Return” (2019), a woman’s portrait is heavy with meaningful, life-affirming symbols — birds in flight, flowers, and a multi-pointed architectural detail often associated with Middle Eastern domestic spaces. In the lower right corner, small figures bearing heavy packs reference powerful photographs of Palestinians who were expelled by incipient Israeli forces beginning in 1948. Khatib’s luminous figure could represent the generations of Palestinians born after the Nakba, who persevere despite generational trauma and work for the right of return.

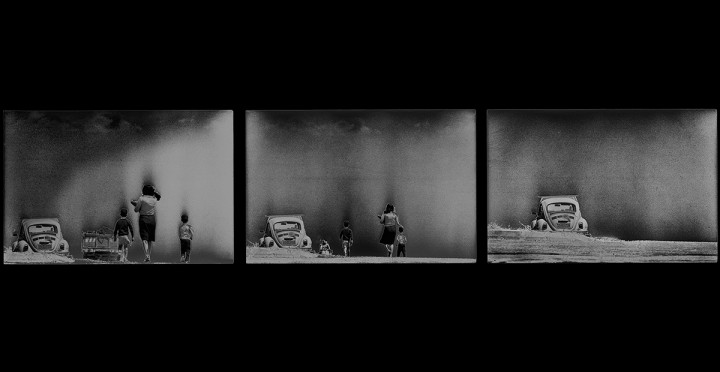

Photographs by Najib Joe Hakim and Yazan Khalili evoke landscape directly. Hakim, a San Francisco resident, produced “Palestine Diary” in the late 1970s while studying at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University. The triptychs “Arab Bus” and “Horizon” (1978-79) capture what look like mundane urban scenes, but they do not convey the harassment and restricted movement Palestinians face day-to-day. “Unsettled” (1978-79) conveys, in four photographs, the rhythms of bedouin life set against settlement incursion. At a glance, a paved road cutting across the hillside may not arouse suspicion, but it is an indicator that Israeli settlements will soon be erected on Palestinian land. Hakim invites us to witness what is blissfully ordinary about Palestinian life and prompts us to recognize how and by whom it is endangered.

In 2010, Yazan Khalili produced “Landscape of Darkness,” a series that recalls his clandestine journey from Birzeit to Yaffa in Israel in 2002. In darkness, Khalili recognizes a physical and metaphorical landscape that is unknowable. “Landscape of Darkness” punctuates that unknown as it portrays light cast over Israeli settlements, but not adjacent Palestinian villages. Where one population enjoys resources such as clean water, continuous electricity, and the relative safety of well-lit streets, the other, by punitive design, does not. Notably absent from Khalili’s starkly beautiful compositions is the twenty-one-foot tall cement barrier that separates Palestinians living in the West Bank from family and communities living beyond it. The apartheid wall, often called such for the cultural and ethnic divisions it enforces, is the most notable landmark in a region steeped in ancient history. Khalili’s refusal to photograph it is an act of defiance.

Preoccupations is one of six exhibitions, all addressing landscape, staged by the Institute Of advanced Uncertainty at Minnesota Street Project. Though the Institute Of advanced Uncertainty — described by Rand as “showcasing trajectories of the creative process” — is mission-driven to celebrate work in progress, the objects and ideas that comprise Preoccupations are far from incomplete. Zarur marshals seven artists’ passionate interpretations of Palestine, be it a lived or imagined experience. The invitation to explore that territory is ours for the taking.